By John W. Fountain

A CARAVAN OF HUMANITY. A PEOPLE OF faith. It idles on 78th Place near Racine Avenue in the warm evening sun one late-summer Friday in June. Music blares from a shiny green SUV outfitted with loud speakers that will lead them on their sojourn in the streets of the South Side of Chicago from the doorsteps of the Faith Community of St. Sabina. It is a spiritual showdown against the forces of darkness.

A bout for the soul of the city, maybe even the bold makings of a revolution that will not be televised. In one corner stands Faith. In the other: Violence.

Which will win?

Two reporters set out last summer to chronicle their journey, covering every single march over 12 hot and muggy weeks in Chicago, through the elements, even as nightfall consumes the last light of day. Chronicling the hope and also the marchers' pain—through the glaring sun and summer rain that would take this caravan of faith to perilous street corners, where, just hours earlier, bullets reigned. Where the wounded had lain, felled by a shooter's deadly aim.

Before summer’s end, this group of the faithful would come face to face with the Death Angel who came to claim even one of their own. And more than one mother would be welcomed into the unenviable club of being mother to a murdered son.

In the end, the summer’s violence would prove to be a foreshadow of one of the city’s deadliest years on record.

But might prayer and faith work in the fight to end violence?

_________________________

_________________________

“Church is the ‘huddle’ of the game... No one comes to a game to see the huddle but look to see what they will do when they leave the huddle to build the Kingdom of God.” -Father Pfleger

_________________________

_________________________

Genesis

|

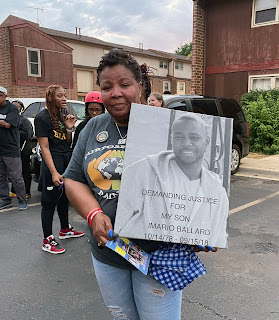

| One of the peace marchers holds a portrait of a slain son during summer 2021. |

They pray before beginning their pre-determined route. Marchers assemble in the 1200 block of West 78th Place, near idling police squad cars and St. Sabina’s lead green SUV, which broadcasts their mission in word and song into the summer wind.

And they march. Through the surrounding neighborhood, up and down humid busy avenues and streets, turning corners onto blocks where shooting and gang violence make life hard, fragile and damn near untenable. They sing, chant, pray, and hand out fliers about social, educational and job services available at St. Sabina.

They greet people on the street, or others who gaze from yards and doorways. The marchers wave back, smile, hug—an intimate exchange of goodwill between strangers. Along the way, Pfleger’s voice blares as he extols the message of hope and peace.

The peace caravan snakes through the neighborhood then finally returns to outside St. Sabina. Pfleger speaks briefly, encouraging marchers for their commitment. They pray again then climb into their cars, the evening turned to night. They head home.

|

| 6th District Commander Senora Ben and officers from the Gresham Police District were a constant presence during the marches, providing an escort for marchers through busy South Side streets. |

No delegation of concerned U.S. congressmen from Illinois. No Cook County state’s attorney. No Cook County commissioner. No chief judge. No governor of Illinois. No Cardinal Blase Cupich of the Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago, or any detectable representation from its other 289 parishes.

No assemblage of members from the countless denominations that dot the urban landscape well beyond St. Sabina—an English gothic cathedral built in the early 1930s and once an Irish Catholic parish with a well-documented history of resisting integration by Blacks during the 1960s whose numbers by then in Chicago had swelled significantly due to the Great Migration.

There is no sighting of any U.S. presidential delegation, or of any “cavalry” coming to assist a grassroots effort to deliver its community from the forces of evil. No sense that in this city, population 2.75 million, there exists any grand urgency or the collective will to work together to resolve the issue of violence, which disproportionately impacts Black and brown communities.

The absence of city, county and state officials from St. Sabina’s marches doesn’t mean they aren’t doing anything to quell the city’s violence and murder. But it also does not reflect any visible concerted commitment to this grassroots effort, perhaps the largest, most consistent and most vigilant by any church or pastor in Chicago—a city that by year’s end would record more than 3,500 shootings, police records show.

Moreover, Chicago accounted for 836 of the county’s 1,087 homicides recorded in 2021—1,002 of them gun-related, according to the Cook County Medical Examiner’s office. The county’s gun-related homicides in 2021 broke the previous record of 881 recorded in 2020, marking an 8.5 percent increase—evidence of a rise in violence and the need, many here say, for solutions. Now.

The absence of other churches to partner in St. Sabina’s effort—or in another perhaps by their own initiative that might help create a seismic movement within the community of faith to redeem the soul of a city where the blood of women and children stain its most menacing streets—is inexcusable. And the church’s overall laxity—particularly the Black church—to collectively and significantly seek to move beyond its walls to address the city’s violence, which cannot be solved by policing or policy alone, is downright shameful.

But the question for me, amid an unrelenting storm of violence that bangs louder than any gunshot is: Where is the church?

This much is clear: St. Sabina is out here in these streets. And they believe that prayer is not a negligible thing. Not the only step needed to reclaim community. But perhaps a good first step in seeking to shift a prevailing atmosphere where the spirit of evil is manifested in the natural as murder and mayhem, and requires divine intervention.

“What makes us authentic Christians is not what we do in the church building but what we do when we leave because we have gathered,” Pfleger explained.

“Church is the ‘huddle’ of the game... No one comes to a game to see the huddle but look to see what they will do when they leave the huddle to build the Kingdom of God.”

|

| Father Pfleger chats with brothers on the street during one of the Friday Peace Marches, offering job services and counseling at the Faith Community of St. Sabina. |

On one particular Friday, Pfleger breaks off from his point position in the march. He hurries, wearing his white high-top canvass Converse and black-and-white anti-violence sweatshirt, over to a group of brothers on the sidewalk while flanked by men of St. Sabina.

The smell of marijuana wafts in the wind, like the warm greeting from the white Catholic priest with a reputation in the streets as a down-to-earth preacher with a genuine love for the hood. But this is their block. The preacher’s sudden appearance out of nowhere clearly is not on their agenda and apparently no reason to breach their leisurely activities as one young man continues rolling what appears to be a blunt throughout the entire exchange.

But there is no judgement. No airs. No wincing from Pfleger who straightway launches into a cordial appeal.

Not an appeal for a contribution to a building fund. Not a membership drive. Only mutual respect. And for Pfleger perhaps a chance to save a life, win a soul.

“Come talk to us, maybe we can help,” he says to a group of young men who look to be in their early 20s. “Maybe we can help, all right?”

One young man nods.

“So come see me,” Pfleger says, turning to another standing nearby, wearing a goatee and an untied black do-rag on his head and giving the preacher the side-eye. His skepticism about the preacher’s promises is clear. Pfleger senses as much.

“Don’t be like that, looking at me like I’m bullshitting you,” Pfleger says. “I’m telling you the truth. I’m here, ok?” he assures the young man, placing his right hand on his shoulder.

“Ok,” the young man says, nodding, looking directly into the preacher’s eyes. “I got you.”

They both smile, shake hands, embrace.

“I love you, my brother,” Pfleger tells him before pushing on. “I want you to be safe.

“Too much up in here for the world not to hear from,” Pfleger says, gently tapping the left side of the young man’s head. “OK?”

The young man nods.

Prayer changes things. Or does it, really?

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote: “There can be no gainsaying of the fact that prayer is as natural to the human organism as the rising of the sun is to the cosmic order… Men have often tried to dismiss it by affirming that pressing rigidity of natural law makes it impossible. But such a declaration is unconvincing; for there is something deep down within us that makes us know that God works in a paradox of unpredictable newness and trustworthy faithfulness.

“And so even the most devout atheist will at times cry out for the God that his theory denies. Men always have prayed and men always will pray.”

But can prayer actually affect the affairs, lives, behavior, or health of humans? Can prayer be used to impact the condition of neighborhoods besieged by gun violence and murder?

Might a solution to violence in a natural world lie, in part, also in a more spiritual approach aimed at shifting the values, attitudes, mindset and cultural atmosphere in which so many communities have been turned into war zones, where bullets fly, children die and their blood stains city streets?

That is debatable. But the use of prayer for divine intervention into earthly matters is not new. For example, Americans—religious and nonreligious—amid the vast uncertainty and crises wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic have turned to prayer.

In fact, a Pew Research Center study in March 2020 found that more than half of all U.S. adults or 55 percent said they have prayed for an end to the spread of coronavirus. The study also found that a significant majority of all Americans who pray daily—or 86 percent—have turned to prayer during the Coronavirus pandemic. Additionally, a significant number of Americans who say they have seldom—or never prayed (15 percent)—have also turned to prayer. Even among those who do not belong to any religious group, 24 percent admitted to praying to a higher power, the Pew study found.

Studies on the effectiveness of prayer have found largely that it works as a good kind of spiritual meditation, but have found no quantifiable evidence of divine intervention invoked by prayer.

“Clearly, people pray because it makes them feel better, or makes them feel hope, or makes them feel love, or makes them feel just a welcomed hair shy of being utterly powerless,” Phil Zuckerman writes in a 2019 Psychology Today report. “So, concerning all of the above, it can be said that prayer works.

“But when it comes to prayer as a form of asking for something from a divine source and then getting it—there is simply no empirical evidence that such mental messaging to an invisible deity works. All stories of ‘answered prayers’ are merely anecdotal, and nothing more.”

Believers, however, have a different opinion. They attribute everything from healing from cancer and other diseases and drug addictions to their deliverance from any number of life crises, emergencies and dilemmas—from major to the minor—to divine intervention, stemming from prayers.

Faith is “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things unseen,” believers are quick to say, citing Hebrews 11:1. And the effectiveness of prayer and faith—both intangible, invisible, spiritual and not easily quantifiable—difficult to prove, yet as difficult to disprove.

|

| Ashley Adams, mother of Marquise Richardson, 14, is comforted on the stairs of The Faith Community of St. Sabina where her son’s funeral service was held |

“I believe in the power of prayer,” Pfleger told me. “It is what grounds us and reminds us we are not just doing some action rather we are doing it in Faith and walking with the power of God with us.

“I also believe Faith without works is dead,” Pfleger said. “So it is prayer and then walking and living out our prayers.”

|

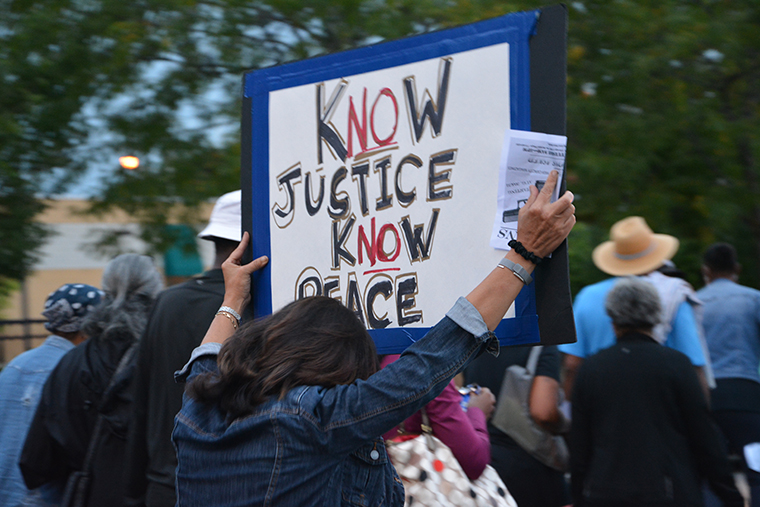

| A woman holds a sign for peace during St. Sabina’s march for peace in summer 2021. |

Lamentations

They appear, at first glance, an unintimidating force. A mixed, mostly Black congregation, led by a white Catholic activist priest. Graying but praying church mothers, babies in strollers. Strong men in T-shirts. Some on crutches or wheelchairs. The infirmed. The wounded. Mothers and fathers of murdered sons and daughters, pressing through their pain for purpose.

They hoist signs proclaiming their mission. Sneakers, walking shoes and wheels. Strollers. Not tanks or guns in this assault against the violence that drenches this city each summer like an unrelenting rain.

On one Friday evening, they kneel at a corner where hours earlier two people were shot. They pray, their fervor as shining as their courage and commitment that leads them on another Friday to an apartment complex known for violence and shootings.

Here, a 10-year-old girl, recovering from being shot, and her parents emerge from their apartment amid the swarm of marchers. Pfleger comforts the daughter and also her mother who lays her head on his shoulder, tears falling. He embraces them as a prayer warrior fills the air with declarations of peace and a petition for blessing and healing for this family.

On another Friday, marchers surround a woman whose left shoulder is still bandage from having been treated for a gunshot wound. Her husband who was also shot is still in surgery, she tells the priest as peace marchers surround her in the yellowish glare of street lights beneath a night sky on a corner on 81st Street.

“We plead the blood of Jesus, we say devil, ‘you are a lie and you will not stop them from fulfilling their destiny,’” a woman prays, clutching a microphone as “hallelujahs” and “thank you, Lord’s” ring out unashamed and unconstrained into the atmosphere.

An atmosphere filled with the unpredictability and the threat of chaos and the unseemly that can erupt without a moment’s notice, like the woman holding a young child the marchers witness as a man kicks her out of his vehicle and drives off, abandoning them in the heat. Pfleger and others rush to her side, offer prayer and the human hand of assistance.

|

| A little girl gets tattoos and her face painted at a back-to-school picnic held at a park by St. Sabina after a summer of peace marches. |

Revelation

For more than a dozen years, the Faith Community of St. Sabina has taken to the streets for a “Summer Peace March.” They pour through Auburn Gresham until summer’s end, seeking to quell violence that grip neighborhoods ¬mainly on the city’s South and West Sides where shell casings often seem more prevalent than the sight of little girls jumping rope.

Chicago’s deadly violence is a reflection of a tale of gangs and social media beefs mostly between young Black and brown men in Black and brown neighborhoods that bear the brunt of that violence. Inarguably, the violence, which leaves a trail of blood and bodies, is more deeply a reflection of systemic racism, of the city’s historic neglect of the poor and of those hyper-segregated neighborhoods that lack resources. Among them: jobs, equality in education, healthcare and housing.

And yet, it is the violence that permeates life in the hood. That makes life more tenuous if not treacherous, and that too often ends in tragic violent tale I too often have covered as a journalist for more than 30 years.

What ought to be clear by now is that any effort to heal, uplift and improve these neighborhoods must be an effort to stop the killing, to subdue the violence so that daily gunfire and murder of the innocent and young are no longer the norm. What ought to be clear is that the violence in some Chicago neighborhoods—though minuscule if at all existent in many others—has become as predictable as the passing and arrival of summer, and that it has reached a critical stage. Clear that Chicago must now engage in an epic war for its soul.

A soul in a city beset by the killing of our children—of little girls like 7-year-old Jaslyn Adams, murdered less than a year ago, about 10 miles from St. Sabina, on the West Side. She was sitting in her father’s car in the drive-thru of a McDonald’s parking lot when gunmen reportedly fired at least 45 shots from an AK-47, fatally shooting Jaslyn multiple times and also wounding her father.

Once upon a time chief crime reporter at one of Chicago’s big daily newspapers, I have come to take the pulse of violence in this city not only by the number of those killed each year, but by the number of those shot. By the randomness of shootings today. By the current blatant disregard for human life and the collateral of innocents. By the state of brazenness of shooters and their youth compared to shooters and gangs in days of old who respected innocents and abided by a gang code. By the easy access to high-powered automatic weapons that enable the unleashing of mass destruction in a matter of just seconds.

And by my measurement, Chicago’s violence is worse than it has ever been. Chicago no longer has a conscience. Chicago is on the verge of losing its soul.

I know of no institution better equipped to save souls than the church. And I know of no church or pastor in this city more willing to engage in the effort at a grassroots level to try and reach the heart, mind and soul of a community besieged by evil, violence, poverty, trauma and hopelessness than St. Sabina and Father Michael L. Pfleger. A church that even amid its grand net of social services sees its most formidable weapon in this war as: faith and prayer, fueled by the audacity of hope.

I bore witness to that hope last summer—infectious and freely given. Witness to the smiles that hope, love and faith caused to spread over the faces of even hardened young brothers who stood on some of the city’s meanest streets as the Peace caravan passed by and the church paused to embrace them.

I witnessed the miracle of a church in modern times, flowing freely beyond its walls, seeking to impact community. Talking the talk and walking the walk. Seeking to be the hands, feet and heart of Christ, and to affect change: one step, one prayer, one block at a time.

So what did all that accomplish? Where’s the evidence that all that marching did one bit of good?

“What I know is that it gave people hope,” Pfleger told me months later in hindsight. “We got so many folks thanking us. It also impacted the community with joy, love, and light amidst the darkness.

“We were able to get out information about our services, which each week would have folks come for help. It also brought some young brothers to us who wanted a change,” Pfleger added. “We were able to help them, mentor them and get many jobs... Those are things I know.”

“Only God knows what the seeds planted will harvest.”

This much I know: That I witnessed by their human presence and engagement the hand of God. I felt in their uttered summer prayers a power that flowed like an electrical surge, ushering in an almost tangible spirit of peace in the streets along their trail.

And I saw in the eyes of those they touched: tears, joy, relief and gratefulness that in a city where so many do nothing to try and end this scourge called violence, the church—this church—cared enough to do something.

Indeed on hot Friday nights—in a bloody city on the verge of losing its soul—by the St. Sabina caravan of believers, the seeds of peace were sown. All summer long.

“Invasion of Faith: Faith vs. Violence” is a multimedia journalism project by John W. Fountain and Samantha Latson, a graduate journalism student at Indiana University.

|

| Peace Marchers walk during St. Sabina's "Summer Invasion" 2021 |